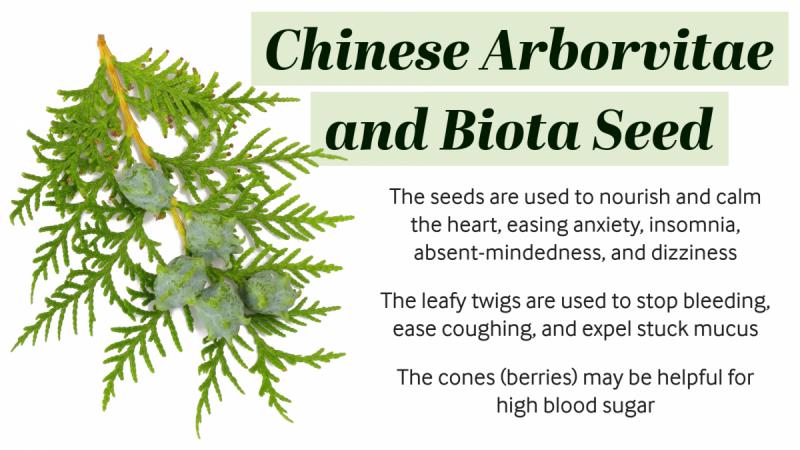

In front of my childhood home, on either side of the front porch, were two Chinese arborvitae trees. These trees are popular for landscaping because they can be nicely shaped. However, even when I started learning about the edible and medicinal properties of plants around me, I never considered that the two trees growing right on my doorstep might have any medicinal value. It wasn't until I was trying to solve a minor mystery that I started to conjecture that the trees could be helpful for high blood sugar levels.

Juniper, Cedar, and Arborvitae

It happened in the late 1980s when I was reading an article about juniper berries in a local holistic newspaper I got at the co-op. It was by the famous Utah herbalist John Christopher. A man came to him with edema and he recommended juniper berry tea for him. The man returned a couple of weeks later and reported that the tea hadn’t worked. Surprised, Dr. Christopher asked him to show him the berries he’d been using. When the man did so, he said, those aren’t juniper berries they are cedar berries.

It happened in the late 1980s when I was reading an article about juniper berries in a local holistic newspaper I got at the co-op. It was by the famous Utah herbalist John Christopher. A man came to him with edema and he recommended juniper berry tea for him. The man returned a couple of weeks later and reported that the tea hadn’t worked. Surprised, Dr. Christopher asked him to show him the berries he’d been using. When the man did so, he said, those aren’t juniper berries they are cedar berries.

When Dr. Christopher showed him the correct remedy, the man said that he was going to continue taking the cedar berry tea anyway. When Dr. Christopher asked why, he responded that they were helping his blood sugar.

I found the story interesting, but parts of it didn't make sense to me. At the time most herbalists believed that the cedar berries in the story would have come from a different species of juniper that had been misnamed cedar by Utah pioneers, Juniperus ostosperma, which is now called the Utah juniper.

The first mystery I saw in this story was that Utah juniper berries should have had a diuretic effect. After all, Native Americans used the Utah juniper for kidney ailments. So what plant did the man gather berries from that lowered his blood sugar but didn't help his edema?

The second mystery was that the cones (berries) from several different species of juniper would be hard to tell apart. I’d have a hard time telling a juniper tree apart from a Utah juniper just from the cones. So, if it was easy to spot that they weren't juniper berries, I wondered if the man hadn’t just gotten the wrong species of juniper but had harvested the cones from an entirely different plant that had berries that were similar but still distinct.

My Theory About Arborvitae Cones

So, I thought to myself, what common plants might a person with no training in botany mistake for a juniper tree? I considered the thuja trees, some of which are also called cedars, as likely candidates. These include the Western red cedar, Thuja plicata, and the Eastern arborvitae or white cedar, Thuja occidentalis.

But my number one suspect for the man's mystery blood sugar remedy at the time was Chinese arborvitae, Playcladus orientalis, which at that time was named Thuja orientalis. Even though I didn't know of any medicinal uses for arborvitae, it was a common landscaping plant, easy to get ahold of and, it could easily be mistaken as a juniper by someone without an understanding of botany.

Arborvitae and Blood Sugar

I didn't have the chance to test my theory about Chinese arborvate as the "cedar berries" that had lowered the man's blood sugar until the early 1990s. At that time, I had a small herb company that made glycerites. After checking to make sure they weren’t poisonous, we made a glycerite from the slightly whole, unripe arborvitae cones. We gathered the cones and crushed them to break them open, but didn’t try to grind them up. We then made a blood sugar formula using the cones as a key ingredient and allowed people to test it. We got very positive reports, including one from a parent with a child with type 1 diabetes. While this doesn't prove that the mystery berries in the story were arborvitae cones all the evidence fits. I would love to see other herbalists test out this use for arborvitae cones and let me know if it also works for them, too. It would also be interesting to see if the Eastern arborvitae cones had similar properties. And as I was to later find out there were known medicinal uses for other parts of Chinese arborvitae.

Biota Seed

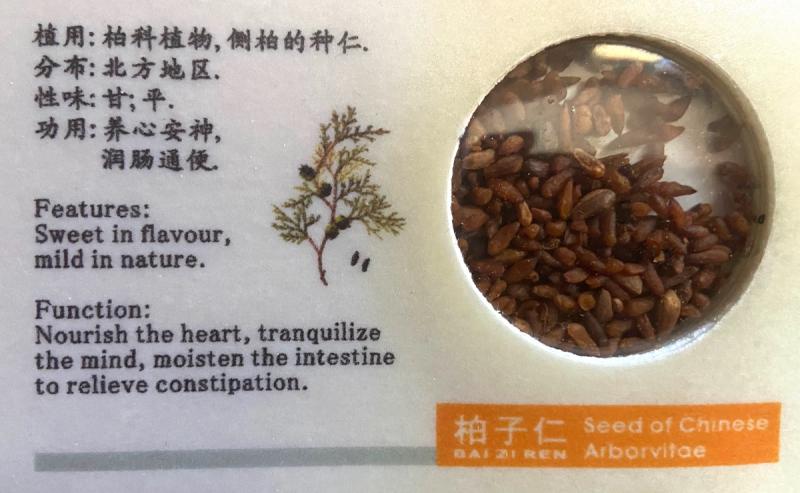

It was over ten years later before I actually found information in books about using Chinese arborvitae medicinally. I was researching an ingredient called biota seed found in a Chinese herb formula for increasing the fire element or tonifying the heart yin. It turns out that biota seeds come from the Chinese arborvitae. This remedy isn’t the unripe cones, which we were using, but the seeds from the ripe cones.

It was over ten years later before I actually found information in books about using Chinese arborvitae medicinally. I was researching an ingredient called biota seed found in a Chinese herb formula for increasing the fire element or tonifying the heart yin. It turns out that biota seeds come from the Chinese arborvitae. This remedy isn’t the unripe cones, which we were using, but the seeds from the ripe cones.

In TCM terms, biota seed is used to nourish the heart and calm the spirit (shen). It’s helpful for anxiety, dizziness, absent-mindedness, and insecurity. It’s helpful for heart problems caused by excessive worry or anxiety such as heart palpitations or those tense feelings on the left side of your chest you get when you’re overly stressed. It also helps insomnia and night sweats. Biota is often combined with schizandra, zizyphus, and/or poria to nourish the heart when it’s being adversely affected by what we call in the West burnout due to long-term stress.

Biota seed is rich in lipids and has a lubricating effect on the stools. It’s helpful for constipation associated with dry stools. In TCM terms, constipation associated with yin deficiency or blood deficiency, which often happens in the elderly. It lubricates the stools in much the same manner as freshly ground flax or hempseeds would.

Arborvitae Leaves

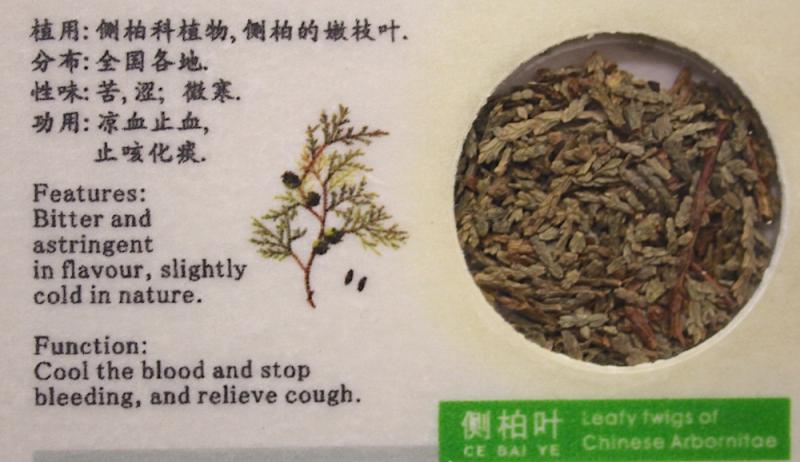

The leafy twigs of arborvitae are also used in TCM. It is considered a bitter and astringent remedy with a cooling effect. It is hemostatic, antitussive, expectorant, and sedative. Its primary use is to stop bleeding. It is used topically as a styptic and internally to help with problems like hematemesis (vomiting of blood), hematuria (blood in the urine), hematochezia (blood in the stool), and heavy menstrual bleeding. For all of these conditions, it is typically combined with other herbs.

The leafy twigs of arborvitae are also used in TCM. It is considered a bitter and astringent remedy with a cooling effect. It is hemostatic, antitussive, expectorant, and sedative. Its primary use is to stop bleeding. It is used topically as a styptic and internally to help with problems like hematemesis (vomiting of blood), hematuria (blood in the urine), hematochezia (blood in the stool), and heavy menstrual bleeding. For all of these conditions, it is typically combined with other herbs.

The herb is also used to expel mucus and stop excessive coughing. It has been used to treat whooping cough and tuberculosis. Again, it would typically be used in combination with other herbs for this purpose. A decoction is used topically on the scalp for hair loss associated with oily hair and itchy scalp.

While an essential oil of Chinese arborvitae is not readily available, you can get it if you search for it. What's more readily available is the essential oil of the Eastern arborvitae (Thuja occidentalis). It has similar properties and uses. The oil is a good one to inhale for damp and croupy coughs as it helps to dispel mucus and calm the cough reflex. The oil needs to be used with caution, as it has a high thujone content, which can produce toxic effects in larger quantities.

Using Chinese Arborvitae

Other than perhaps finding biota seeds as a single or in a formula, you’re not likely to find this remedy available commercially. An internet search brought up very little. However, since this plant is so commonly grown as an ornamental shrub and because of its potential for blood sugar problems I’ve shared this information so you can experiment with it if you’d like. It would certainly be a good remedy to keep in mind for emergency preparedness.

Other than perhaps finding biota seeds as a single or in a formula, you’re not likely to find this remedy available commercially. An internet search brought up very little. However, since this plant is so commonly grown as an ornamental shrub and because of its potential for blood sugar problems I’ve shared this information so you can experiment with it if you’d like. It would certainly be a good remedy to keep in mind for emergency preparedness.

The seeds can be ground and taken internally for constipation or stress. You could also extract the fresh seeds in alcohol or glycerine. If you’d like to experiment with the cones, gather them when they’re still green or greenish-blue, crush them, and extract them in alcohol or glycerine. For both remedies, I’d start with a dose of 20-40 drops, three times a day.

As for the leafy branches, I have several suggestions. You could put them in boiling hot water and inhale the steam for respiratory problems. You could also decoct them to use them as a hair rinse for itchy and oily scalp. You could also use the decoction internally to help stop bleeding, but I’d only do that in emergency situations. The bleeding disorders previously mentioned can all be signs of very serious health issues, which means you need to get a medical diagnosis and find out what’s really going on so you can properly address the causes.

You could also make a tincture or glycerite of the leaves to use for respiratory infections, chronic coughing, and thick, heavy mucus that’s stuck in the lungs. I’d limit the internal use of the herb to no more than two weeks, however, as it’s a pretty strong remedy. The decoction or extract can also be applied topically to help burns or to help treat infected wounds.

I hope my story about my path of discovery about the Chinese arborvitae has inspired you to be willing to experiment with this herb. Studying herbal medicine can be extremely fascinating. You never know when you’re going to discover something new. I also encourage you to not blindly trust what you read or hear, even from a well-known herbalist. Do your own research and constantly test and evaluate what you learn. Finally, if any of you do experiment with the Chinese arborvitae I'd love to hear about your experiences.

Downloads

Steven's Articles

-

-

Eucommia Bark

A superior tonic that promotes kidney, structural,…

January

-

-

Goldenthread, Phellodendron, and Yellow Root

Three herbal remedies containing the infection-fighting…

-

-

Teasel

A traditional herb for healing bones and joints…

-

-

Barberry and Healthy Personal Boundaries

A thorny shrub for fighting infections and supporting…

December

-

-

The Evidence for Berberine

A yellow alkaloid found in traditional infection-fighting…

-

-

The Sensible Use of Caffeinated Herbs

Kola nuts, guarana, and yerba mate and other herbs…

-

-

The Health Benefits and Problems with Coffee

This popular caffeinated beverage can be beneficial…

October

-

-

Understanding Caffeine & Cellular Adaptation

Preserving the power of caffeine's buzz and the…

September

-

-

Horseradish

A pungent spice for aiding protein metabolism…

-

-

Banaba or Crepe Myrtle

A beautiful tree from Southeast Asia whose leaves…

August

-

-

Monkeyflowers

Flower essences to help see ourselves more clearly…

-

-

Mariposa Lilies

Strengthening the bond between mother and child…

-

-

The Noble Bay Leaf

A common kitchen herb for aiding digestion and…

-

-

Epimedium: Horny Goat Weed

A circulatory stimulant and kidney yang tonic…

July

-

-

The Medicinal and Nutritional Benefits of Apricots

A nutritious fruit and valuable medicinal seed for coughs